THE SAHU JAINS OF NAJIBABAD

From managing a slew of mills to owning them and then metamorphosing into some of the greatest entrepreneurs that the country had seen, brothers Shanti Prasad and Shriyans Prasad Jain’s achievements are worthy of many an adulatory epithet. This tribute encapsulates a few to bring out the extraordinary calibre of the duo.

In what began as an English newspaper intended for the British residents of western India in 1838, The Times Group has come a long way to sprawl the Indian media horizon with communication vehicles of almost every description. Among these include newspapers, periodicals, television channels, radio stations, digital content, internet and what have you. Ironically, for a media behemoth that churns out bales and bales of news content every day, updating readers with almost every major development in the public and corporate domains, the story of its own rise remains relatively obscure, with little information available about the group’s early days or its phenomenal growth under its present owners, the Sahu Jains of Najibabad. Yet Bennett, Coleman & Co Ltd (BCCL), as The Times Group is also known, counts among the oldest and most renowned institutions of the country, which makes its architects, especially Sahu Shanti Prasad Jain, deserving of this tribute. Likewise, his brother Sahu Shriyans Prasad Jain’s contributions as a businessman, parliamentarian and philanthropist too deserves commendation.

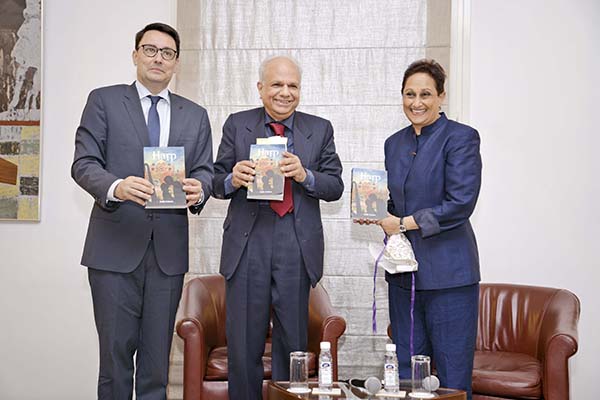

This account, however, would not have been possible without the invaluable help of the Sahu Jain clan, especially Sahu Akhilesh Jain (the present managing trustee of Bharatiya Jnanpith and the president of Akhil Bharatvarshiya Digambar Jain Parishad) and the 97-year-old Sahu Jinendra Kumar Jain, who is the oldest surviving member of the clan. Inputs provided graciously by Ramkrishna Dalmia’s son, VN Dalmia (of Dalmia Continental Pvt Ltd) and Sahu Shriyans Prasad Jain’s grandson, Bakul K Jain, who now is one of the managing directors of DCW Ltd (formerly Dhrangadhra Chemical Works Ltd), have also been immensely helpful.

The Sahu Jains of Najibabad

Age may have taken its toll on Sahu Jinendra Kumar Jain’s hearing, but his voice is as loud and clear as ever and so is his memory of the glory days of the Sahu Jains in Najibabad and the pre-and post-Independence years which marked Shanti Prasad Jain’s rise as an industrialist.

The story that emerges as Jinendra Jain speaks is that the Sahu Jains were a prosperous family of zamindars, whose most illustrious member, Rai Bahadur Sahu Jagmandar Das Jain (father of Sahu Ramesh Chandra Jain) was an “honorary munsif” (honorary magistrate) and a treasurer for the government, who would resolve difficult social and religious disputes at his residence which also served as a court. He remained the chairman of the Bijnore District Board for six consecutive years in the early twentieth century and was held in high regard by both British government officials and the local populace. He is said to have been also philanthropic and would help youth secure government jobs and scholarships for higher studies.

But it is Rai Bahadur Jagmandar Das’ grandfather, Sahu Salek Chand Jain, a pious, philanthropic and well-to-do businessman, to whom the Sahu Jain clan traces its lineage—or at least that part of the ancestry that connects them to Najibabad. Sahu Salek Chand had three sons—Mussadi Lal Jain, Diwan Singh Jain and Jwala Sahai—of whom Sahu Diwan Singh was the father of Sahu Shanti Prasad and Sahu Shriyans Prasad Jain. Sahu Mussadi Lal Jain had four sons, the eldest of whom was Rai Bahadur Jagmandar Das. The others were Ram Swaroop, Moolchand and Sumat Prasad Jain. Sahu Sumat Prasad, the youngest of the lot, was the father of Jinendra Kumar Jain, who now resides in Delhi, where we met him.

The rise of Shanti Prasad Jain

Sahu Shanti Prasad Jain might have been born to a family of landlords and financiers, but most of his wealth had come off his own bat, with of course, the hand of fate playing a role in it. His father, Diwan Singh Jain had died early and this perhaps was responsible in a way for the course of events that shaped his future. According to Jinendra Jain, Shanti Prasad Jain’s elder brother, Shriyans Prasad (1908–92) was adopted by one Ganeshi Lalji; and as for Shanti Prasad, he went off in pursuit of higher studies, part of which happened at the Banaras Hindu University and part of it at Agra University.

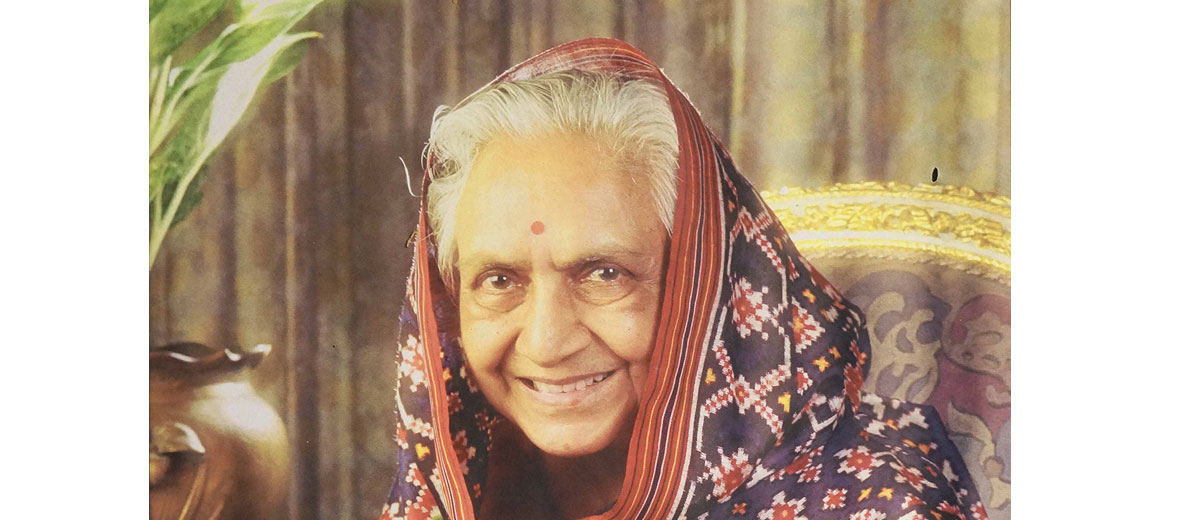

Around 1932, his family responded to a matrimonial advertisement, as a result of which he married Rama Dalmia, the daughter of legendary industrialist Ramkrishna Dalmia. Rama Dalmia supposedly appealed to Sahu Shanti Prasad for her simple ways, Gandhian upbringing and culture and her love for literature. With her husband’s support she later founded the Bharatiya Jnanpith (a literary and research body established in 1944, in Banaras, to promote creative Indian literature) and some of The Times Group’s vernacular titles.

Shanti Prasad was gifted in matters of finance, economics and commerce, and this made him a perfect candidate for managing Dalmia’s growing business empire, as his son-in-law and business partner, along with Dalmia’s younger brother Jaidayal. Soon after his marriage, he, therefore, left for Bihar, to manage a sugar mill that Dalmia had just set up in the Patna district of Bihar. Over the course of time, Dalmia pulled in other relatives of Shanti Prasad to assist him in his expanding business. Among them were Shanti Prasad Jain’s elder brother Shriyans Prasad and Rajendra Kumar Jain, son of Shanti Prasad’s maternal uncle. Shriyans Prasad was assigned to the Lahore headquarters of Dalmia’s Bharat Insurance Company Ltd, and Rajendra Kumar Jain was tasked with the supervision of Bharat Bank Ltd, Delhi Flour Mills and other activities in Delhi.

Over the next decade, the Dalmia-Jain Group grew in leaps and bounds to own a number of sugar mills and cement plants across the country, in addition to textile mills, banks, insurance companies, chemical plants (including Dhrangadhra Chemical Works), food product companies, coal mines, media houses (including Bennett Coleman & Co Ltd), airlines, railways, jute mills, etc. In 1939, World War II broke out, with which fortunes multiplied to make the Dalmia-Jain conglomerate next to only the Birlas and the Tatas in terms of size, scope and wealth. Many of the group companies were in Dalmianagar, as the industrial complex in Dehri-on-Sone came to be known, and were owned by Rohtas Industries Ltd.

Meanwhile, in Lahore, Shriyans Prasad ran into trouble with the British government after he was charged with clandestinely offering shelter to freedom fighter (and future political personality in Independent India) Jayaprakash Narayan at his residence one evening. Jayaprakash Narayan at the time was a fugitive who had fled to Lahore after being pursued by the British government (this was during the Quit India movement). The incident was to result in Shriyans Prasad’s expulsion from Punjab by the British government.

After leaving Punjab, Shriyans Prasad settled in Bombay (now Mumbai) where he rose to supervise the group’s concerns in the Central Provinces, the Bombay Presidency and South India—mainly the Bombay wing of the Bharat Insurance Company, the textile mills located in Bombay and Dhrangadhra Chemical Works in Gujarat (which operated from the Bharat Insurance Building at Horniman Circle). While about it, he also started taking interest in parliamentary affairs. Adept in public relations, he was elected to the Rajya Sabha during 1952-58.

Going solo

Just after Independence, surprisingly, the three main promoters of the group—Ramkrishna Dalmia, his brother Jaidayal Dalmia and Shanti Prasad Jain—decided to call it quits and go their separate ways. While some say this was the fallout of the three stake holders’ differing styles of functioning, others, including Jinendra Jain, attribute it to the controversies kicked up by Dalmia’s multiple marriages and his inherent inclination to take increasing risks in a never-ending quest to grow faster. Whatever be the reason, in 1948, the entire gamut of companies under the Dalmia-Jain banner was divided amicably, with Shanti Prasad Jain getting Rohtas Industries Ltd and several other group companies. Separately, but broadly under Shanti Prasad’s share, his brother Shriyans Prasad got Dhrangadhra Chemical Works. As for Rajendra Kumar Jain, going by Dalmia’s autobiography, he was given `2 lakh as reward. Later, however, Rajendra Kumar requested Dalmia to sell him the shares of Delhi Flour Mills for `2 lakh, which Dalmia did.

After the division, Sahu Shanti Prasad Jain went on to acquire new companies, which along with those under Rohtas Industries were controlled by the newly formed Sahu-Jain managing agency. His now independent business empire, the Sahu-Jain Group, comprised a sugar factory, a plywood factory, a vanaspati plant, a cement plant and a power plant. The group’s finances were ably managed by clansman Sahu Shital Prasad Jain, the son of Sahu Ram Swaroop Jain.

Shriyans Prasad too furthered his business interests by acquiring a textile mill, a wire rope company and a cutlery unit, which together constituted the SP Jain Group (Shriyans Prasad Jain Group). A footwear company called Carona Sahu Company was also set up in Bombay, which was managed by his son Gyan Chand. The company was to later induct the Khataus and the Ruias (of Phoenix Mills) as partners and finally sold to the Khataus, who renamed it Carona Shoes.

How BCCL changed hands

Ramkrishna Dalmia had an appetite for risk and speculation. Around the mid- fifties, he ran into a huge loss of around three crore rupees after a deal went sour. Out of pocket and under compulsion to pay this enormous amount within the time frame of a few days, as stipulated by the stock exchange, Dalmia resorted to selling the securities of Bharat Insurance to raise the money needed to make the payment. Meanwhile, the government got wind of the incident, following which the matter was investigated and Dalmia was liable for criminal prosecution and arrest. Dalmia raised the money by selling his crown jewels, BCCL and Jaipur Udyog Ltd (Jaipur Udyog owned Asia’s largest cement factory in Sawai Madhopur, Rajasthan) to his son-in-law Shanti Prasad Jain, the only ready buyer at such short notice. The government accepted the offer and took the money but did not let Dalmia off the hook. With this, in 1955, the Sahu Jains acquired ownership of what today is the largest media house in the country.

The Times of India story

The genesis of The Times of India, as a newspaper, goes back to a paper called The Bombay Times and Journal of Commerce which was first published on November 3, 1838. Initially the journal was published only on Wednesdays and Saturdays, under the direction of Raobahadur Narayan Dinanath Velkar, a Maharashtrian reformist. In 1840, the newspaper changed hands for the first time. In 1859, its then editor, Robert Knight, merged The Bombay Times and Journal of Commerce with two other newspapers, Bombay Standard and Chronicle of Western India, and the combined issue was called Bombay Times and Standard. In 1861, Knight merged Bombay Times and Standard again with another paper called Bombay Telegraph & Courier and renamed the new publication The Times of India. In 1880, a weekly edition carrying the week’s main articles was launched, which later came to known as The Illustrated Weekly of India. The paper changed hands several times after this until Thomas Bennett and Frank Morris Coleman acquired it through their joint stock company, Bennett, Coleman & Co Ltd, in 1892. The names of both the newspaper and its holding company stuck and to this day they remain unchanged.

In 1946, Ramkrishna Dalmia approached the then owner of BCCL, offering to purchase the company for two crore rupees. After a brief negotiation, the deal was finalised and with it the ownership of The Times of India changed from English to Indian hands. It remained in Dalmia’s hands until his brush with the law in 1955, after which the paper, as we know, came under Sahu Shanti Prasad’s control. (Punjab National Bank followed a similar trajectory. In 1947, the bank was acquired by Ramkrishna Dalmia. In 1953, its ownership passed on to the Jains, with whom it remained until its nationalisation.)

The making of a media baron

Under an enterprising Shanti Prasad, there was a spurt in BCCL’s growth trajectory, thanks to his efforts to increase the circulations of existing publications and a steady stream of new launches such as Parag (a Hindi children’s magazine) in 1958, Femina (a women’s magazine) in 1959, The Economic Times (a business daily) in 1961 and Maharashtra Times (a Marathi daily) in 1962. All of these, with the exception of Parag, have grown from strength to strength over the years and now count among top ranking titles in terms of both circulation and readership, in their respective genres.

In 1958, Sahu Shanti Prasad too ran into trouble with the law for allegedly bringing foreign currency into the country beyond the permissible limit. Getting wind of what he was up to, law enforcers lay in wait to catch him in the act at Palam airport and arrested him promptly after his plane landed. The government’s contention was that the money being brought in was a refund from a German company, against under-performance of certain machinery that the Jains had purchased from them. The refund was made under the stipulation that the refunded amount could be used to purchase alternative machinery but not taken back to India. The Jains, however, had brought this money to India, which, according to the government was a clear case of violation of foreign exchange regulations that were in place at the time. The case dragged on until reprieve came after a Supreme Court reprimand that Sahu Shanti Prasad Jain was being unjustly persecuted, as all he had done was claim damages from another country, which actually went in India’s favour.

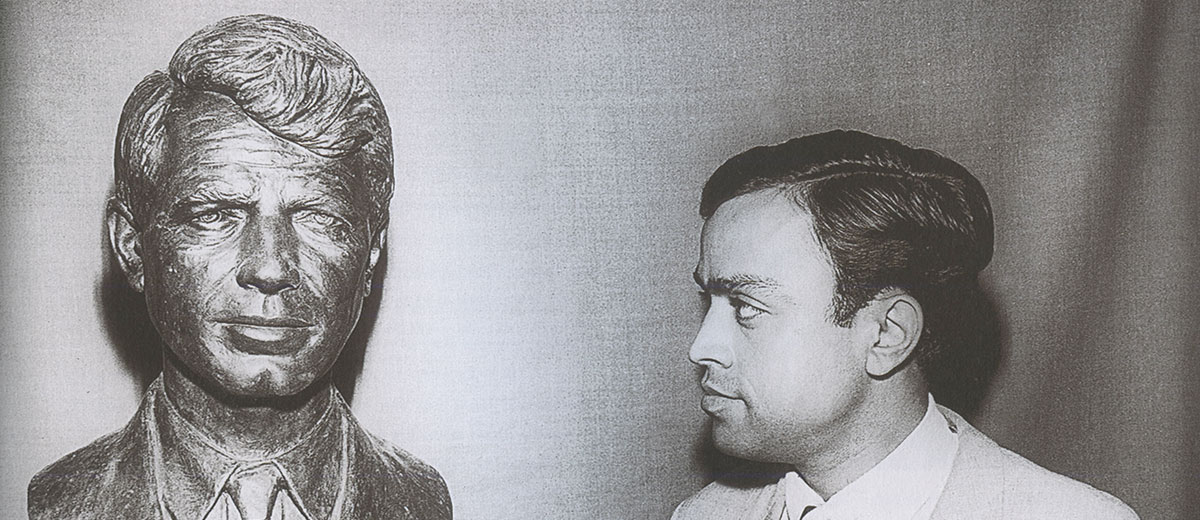

Apart from Shanti Prasad Jain, BCCL’s top management at the time comprised other members of the Sahu Jain clan, a very prominent example being Rai Bahadur Jagmandar Das’ son Sahu Ramesh Chandra Jain (who incidentally is the father of Sahu Akhilesh Jain) who joined the Times of India Group on Sahu Shanti Prasad Jain’s insistence in 1960. He went on to become the executive director of BCCL and also earn the distinction of being the managing editor of The Times of India and the editor of Navbharat Times, two of the Times Group’s most respected titles. He was also the printer and publisher of both the newspapers in Delhi. Further, he was the managing trustee of Bharatiya Jnanpith and served as the president of the Indian Newspaper Society and chairman of the board of directors of the Press Trust of India.

A few years down, in 1969, Sahu Shanti Prasad Jain’s son, Sahu Ashok Jain (1934–99) joined BCCL. Incidentally, around this time (1970s), the Sahu-Jain Group was partitioned and a large chunk of it went to younger son Alok Jain. With this, Alok Jain became the owner of Jaipur Udyog Ltd and several other companies which subsequently came to be collectively known as Alok Udyog. In the nineties, another partition took place between Ashok Kumar Jain and Sahu Shanti Prasad’s third son Manoj Kumar Jain, who later resettled in Austria, where he died. Sahu Shanti Prasad’s daughter, Alka married Bajrang Jalan from Calcutta.

Sahu Ashok Jain’s tenure with the group unfortunately started on a dismal note. The same year he joined, BCCL hit a major roadblock when certain charges with respect to the management of BCCL were brought against the existing board of directors, including Shanti Prasad Jain. Alleging mismanagement, the government sought an annulment of the existing board. The board was eventually disbanded and a court appointed board was instituted that remained at the helm of affairs until 1976. Very little growth if any happened during these years.

The end of an era

A year later, on October 27, 1977, Sahu Shanti Prasad Jain breathed his last. Apart from turning around BCCL’s fortunes, his other noteworthy contributions lay in the field of philanthropy. The establishment of several schools, colleges, research institutes and museums are credited to him. An industrial township in Karachi (now in Pakistan) where the Dalmia Cement plant was located, still goes by the name Shantipuram (after Shanti Prasad Jain).

After BCCL was returned to the Jains by the government in 1976, Sandhya Times, a Hindi tabloid was launched in Delhi in 1979, and the Delhi and Calcutta editions of The Economic Times were also launched. As for Sahu Ashok Jain, jolted by the group’s brush with the law, his approach to managing the group’s affairs as chairman remained cautious and measured, which combined with his traditional Marwari approach to business, nevertheless, helped BCCL to comfortably sail through the years until his demise in 1999. But by then, his sons were well entrenched into the family business. Their innovative ways of doing business were to radically change the way the media house was run, which in turn was to send the group’s fortunes skyrocketing.

Winds of change

By the mid-eighties, the Indian media industry was in a flux. The old order, where editorial opinion and policies were seen as the raison d’être of a newspaper and held sacrosanct, was gradually giving place to a more market-oriented approach. By the late eighties, the industry was to see the beginning of the tectonic changes that were to rewrite the rules of the media business. These changes, many feel, were majorly scripted by Samir Jain, assisted by his brother Vineet Jain. Sensing the pulse of the times, they were able to design growth strategies that emphasised revenue generation through sale of space/time and reinventing editorial policies to facilitate this. This marriage between the two functions was to ring the death knell for the vice like grip that editorial departments earlier held in the running of publications, but result in healthier bottom lines, giving the financial muscle needed for media houses to grow and prosper as profit-making entities, rather than merely exist as news vending gargantuans. With liberalisation and the IT age following, newer avenues of growth presented themselves which again BCCL was quick to capitalise. In all this, the brothers, to an extent, were governed by a do-or-die spirit, as by the eighties most of the Sahu Jains’ other businesses except BCCL were either dead or dying.

In 1992, Sahu Shriyans Prasad Jain breathed his last. During his lifetime, apart from being a Rajya Sabha member, he also had served as the president of the India Chapter of the International Chamber of Commerce and the FICCI (during 1962), and as the president of Bhartiya Jnanpith. Like most other Sahu Jains, he was a philanthropist too and is credited with having founded several educational institutions and trusts. The world renowned S P Jain Sadhana School and Om Creations Trust in Mumbai are part his philanthropic legacy. He was awarded the Padma Bhushan for social work in 1988.

Businesswise, Shriyans Prasad Jain’s company, Dhrangadhra Chemical Works went on to expand by putting up a 2500-acre chemical complex near Tuticorin called Sahupuram, which was spearheaded by his son, Prem Chand. Now known as DCW Ltd, the company continues to flourish under Bakul K Jain. A major producer and exporter of soda ash, DCW Ltd also produces a host of other products that makes it one of India’s fastest growing multi-product multi-location chemical companies.

Shining through

As of today, The Times Group owns a string of dailies and tabloids and scores of periodicals. These apart, the group owns several subsidiaries including Entertainment Network India Ltd (ENIL) that controls the well-known Radio Mirchi and has interests in events, film production, etc; Times Internet Ltd, which is in the business of online news; Times Business Solutions, which operates several websites and portals; World Wide Media, which controls some of the group magazines and related events (such as beauty pageants and awards shows); Brand Capital, which is the investment wing of the Times Group; among others. The group employs over 11,000 people and has posted a turnover of 8,778 crore (US $ 1.3 bn) in FY15. It continues to remain a family controlled business house with the Sahu Jains owning majority stake. The group is headed by Sahu Ashok Jain’s widow, Indu Jain, as chairperson, whose sons Samir Jain (Vice-chairman) and Vineet Jain (Managing Director) continue to propel its growth with the same dynamism with which they turned around its fortunes so dramatically in the eighties and nineties.