Khaitan & Co: Vanguards of the Legal Profession

Reams have been written about Marwaris’ uncanny entrepreneurial acumen and predilection for setting up businesses, which no doubt have been the cornerstones of their overall success as a community. But even as building industries took them up the rungs of success, incepting them and then keeping them well oiled and running meant compliance with the legal framework. It is here that another group of the Marwaris, roused by patriotic fervour and fraternal feelings, felt the need to support their brethren who were beginning to challenge the British stranglehold over the Indian industry in the tumultuous pre-Independence years. Among them was a family from Ramgarh, whose patriarch, Naurangrai Khaitan, in a fortunate stroke of serendipity, propelled one of his sons, Debi Prasad, towards the legal profession, thereby paving the path for setting up the illustrious Khaitan & Co that continues to remain one of the nation’s top law firms over a century later.

The story of Khaitan & Co dates so far back that much of what we know today about the inceptive stages of the company is based on titbits of information gleaned from members of the Khaitan clan, the staff of Khaitan & Co and their friends and associates. Amicus Curiae, a 385-page tome authored by Aditi Roy Ghatak which was published to commemorate Khaitan & Co’s centenary in 2011, sheds light on these aspects.

Law in the blood

It is almost as if the law profession runs in the Khaitans’ genes. A peek into the family’s early history, dating back to the early nineteenth century, reveals that Naurangrai Khaitan’s grandfather, Kewal Ram, was a judge in Fatehpura, a town in the Sikar district of Rajasthan. Unable to put up with the oppressive ways of the local thakurs, he left Fatehpura to resettle in Ramgarh (also in Rajasthan), where his son, Puranmull also took up the legal profession. As fate would have it, Puranmull too had to leave home, whereupon, like so many other Marwaris of his time, he turned eastwards, pitching camp in Purulia in Bengal, where he started a small clothes business together with his brothers. His family, however, stayed back in Ramgarh, where, in 1854, his son Naurangrai was born. Puranmull died soon after Naurangrai’s birth.

A bright spark

Around 1866, when Naurangrai was about 12, he left home to join his uncles in Purulia. Here, one day, in an incident that was to change his life, he ran into Colonel E I Dalton, the deputy commissioner of Purulia, who happened to be on a routine survey of his territory on horseback. Intimidated by his awesome presence, the locals as usual scampered for safety, but an unfazed Naurangrai not just faced the burrasahib but also actually held a stimulating conversation with him, which so enthused the Englishman that he went out of his way to meet his uncles to suggest and even insist that they send Naurangrai for higher education. Naurangrai’s uncles complied. Living up to the colonel’s expectations, not only did Naurangrai go on to perform brilliantly in academics, but at a later date, when the Khaitans’ prosperous family business went bust, he once again greatly impressed Colonel Dalton with his work, after the latter stepped in to help him with a job as a sub-jailer at the Purulia jail. Thereon, Naurangrai went on to become the deputy superintendent of jails—the first Indian to be honoured with the post—and was put in charge of the region’s biggest jail which was in Buxar. So able was he at prison administration work that eminent personalities from the country over, including poet Rabindranath Tagore lavished praise upon him.

As the years wore on, Naurangrai’s fortunes grew with his improving status that brought him widespread respect and honour and also the zamindari in Purulia that the family had lost when their business ran aground. The year 1906 marked the high point of his career when he was conferred the Rai Bahadur title by the British. With his elevated social status, his outlook towards the sociocultural environment of the times changed also. It had him ensure the best possible education for his children—this was a time when education was looked down upon by the Marwari community—and even go so far as to disregard the taboo attached with English education and send his son Debi Prasad to the Buxar District School, where the medium was English.

The founding of an institution

Naurangrai was married to Surya Devi, the daughter of Gulabrai Jhunjhunwala of Jhunjhunu, through whom he had seven sons and four daughters. Among them were eldest son Lakshmi Narayan, who was followed by the four daughters and the remaining six sons, who were Debi Prasad, Kali Prasad, Durga Prasad, Gauri Prasad, Chandi Prasad and Bhagwati Prasad. Debi Prasad, the sixth child and the second son, was born on August 14, in 1888. A brilliant student, he went on to earn a first class first in the entrance examination from the Patna division and also a scholarship that led him to the most hallowed educational institution of the day: the Presidency College of Calcutta (now Kolkata). In time, he was to earn a master’s degree, followed by a bachelor’s degree in law, which put him at the pinnacle of academic achievement. Among his co-students at the Presidency College were some of the most brilliant minds of the time, including Rajendra Prasad, who was to later become the first president of the Republic of India; Badridas Goenka, who was to become the chief architect of the RPG business empire and the first Indian chairman of the Imperial Bank of India (now the State Bank of India); and J N Mazumdar, together with whom, he was to lay the foundation of the iconic Khaitan & Co in 1911.

Debi Prasad Khaitan’s initiation into the world of law actually had its roots in a promise made by the then Governor-General of Bengal to Naurangrai to secure his (Debi Prasad’s) future by making him a district magistrate. In truth, this was an incentive by the governor-general to retain Naurangrai, who was contemplating going back to Rajasthan after his successful tenure as the administrator of prisons in Buxar. With his career path thus chalked out, Debi Prasad turned his focus towards a future as a district magistrate, but fate took him towards attorneyship instead. This happened on the advice of one Ernest Hardwicke Cowie, an inmate in Naurangrai’s jail whose help Naurangrai had sought to write the application to the Inspector of Prisons, indicating his desire to continue with his employment, provided Debi Prasad was made a magistrate. An erstwhile partner in a firm of solicitors and also a member of the Incorporated Law Society, Cowie felt that with Debi Prasad’s excellent academics, it would best serve him to train to be an attorney.

However, no English law firm would employ Debi Prasad as an articled clerk—a preparatory stage for aspiring attorneys. Ultimately, he joined a firm by the name Manuel and Agarwalla, and a few years on, in 1911, cleared his attorneyship examination with flying colours. The next challenge was to secure partnership in a law firm, which again proved difficult with no British firm accepting him. Choosing to start on his own, he began with a few loyal clients (among them was Ghanshyamdas Birla, whose career as a jute baron was still to take off), until his oratorial and argumentative skills earned the admiration of the Chief Justice and those present at the court one day, while fighting a case as a junior, under the legendary Deshbandhu Chittaranjan Das. After hours of cogent arguments, Debi Prasad won the case, which made him an instant hit. Work started pouring in for the Young Turk after this, until emboldened, he teamed up with his college mate J N Mazumdar and set up their own firm at 10, Old Post Office Street, in Calcutta. Khaitan & Co was born. The law profession was held in high esteem in Bengal in those days, and it was a matter of immense pride for Marwaris that one of their own had become an attorney long last.

A swadeshi perspective of law

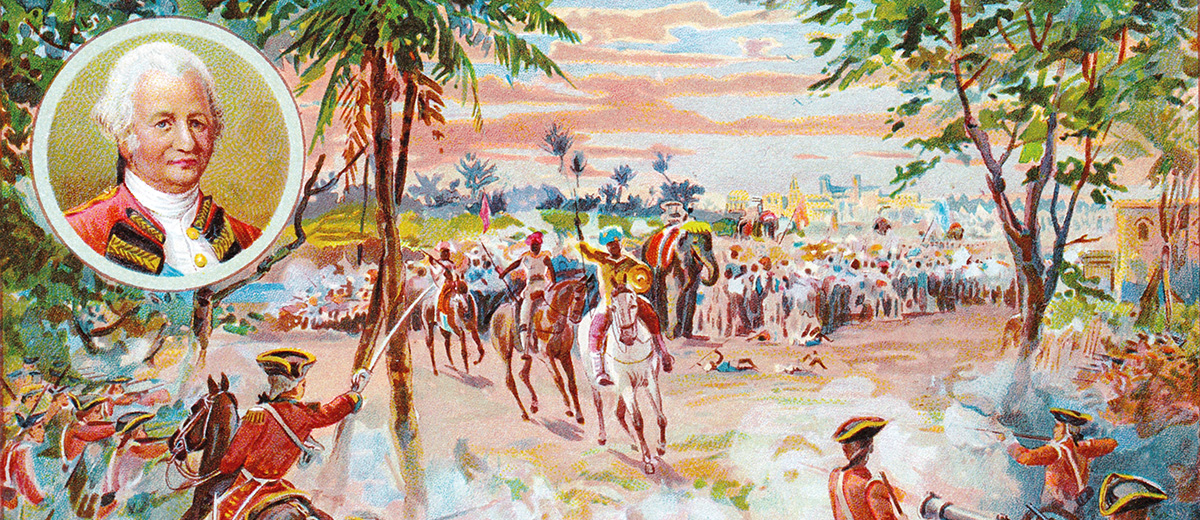

The earliest instances of British law in India date back to early eighteenth century. By the 1770s, the British East India Company had set up courts in several cities, including one in Calcutta in 1774. By the early twentieth century, pushed to the brink by British hegemony, the Indian freedom movement started gathering steam. Among the dreaded instruments of British oppression was a biased judicial system, which roused nationalistic feelings among Indians at large and also sections of the legal fraternity, who resolved to achieve impartiality by perpetrating the existing judicial system with an Indian perspective. Khaitan & Co chose to be among them.

With the swadeshi sentiment sweeping through the nation, this was also a time when the Marwari community of Calcutta started waking up to the need for an indigenous industry, which led to the formation of various bodies like the Marwari Association, the Marwari Chamber of Commerce and The Jute Balers Association. It was in the backdrop of this awakening to the exigencies of the time that Debi Prasad proved his mettle as a top legal counsel. As a business community, internal conflicts of interest were frequent among Marwaris, not to forget their numerous issues with the British administration. This had fellow Marwaris turn to Debi Prasad for legal counsel, which he on his part reciprocated by taking up the cudgels for them, motivated both by fraternal feelings and the need to expand his fledgling business. That he had made himself a part of the powerful Marwari Association by offering his services as a member of its working committee also helped in these dual objectives. Gradually, as the number of clients began to grow, he felt the need for helping hands and turned towards his brothers, who, on their part, inspired by his success, readily obliged by joining hands with him.

The magnificent seven

Among the Khaitan brothers, the eldest was Lakshmi Narayan. When Debi Prasad was born, the Khaitans lived in Burrabazar, a Marwari-dominated business district in Calcutta, where Lakshmi Narayan helped his uncle, Anandi Ram, in his textile and garments business. Debi Prasad, perhaps, would have joined the family textile business too but for the governor general’s promise to Naurangrai to make him a district magistrate, which changed the course of his life. Given that Lakshmi Narayan was considerably older than his other brothers and was already engaged in a different field, he could not go through formal training required for attorneyship, and this stood in the way of his being inducted as a partner in Khaitan & Co. To get the better of the impediment, his younger brothers made him a partner by special agreement, whereupon Lakshmi Narayan became the head of the administrative wing of the firm which he managed very ably. Later, his descendants, however, were to contribute significantly to Khaitan & Co as attorneys, including his son Kishan Prasad and grandsons Nand Gopal Khaitan, Pramod Khaitan and Padam Khaitan and also Padam Khaitan’s daughter, Nandini Khaitan, who is the first woman lawyer from the family to join the firm.

Among the first of the brood to join Debi Prasad as an attorney was younger brother Kali Prasad. The Khaitan brothers providentially were equally blessed when it came to mental abilities, for Kali Prasad too turned out to be a brilliant student, who drew widespread admiration, when he secured a first division in his MA exams. Encouraged by the venerable Sir Ashutosh Mukherjee, a prominent educationist, and other pillars of the Marwari community such as G D Birla and Jamnalal Bajaj, he proceeded to London for his bar exam which was to qualify him as a barrister. After returning from England, Kali Prasad joined the Calcutta bar in 1914 and soon established himself as an able and outstanding member of the legal fraternity, earning the sobriquet of ‘a moving legal encyclopaedia’. His crowning moment, however, came after three brilliant decades of practice, when in 1949 he was appointed advocate-general of West Bengal, the highest office of the state judiciary.

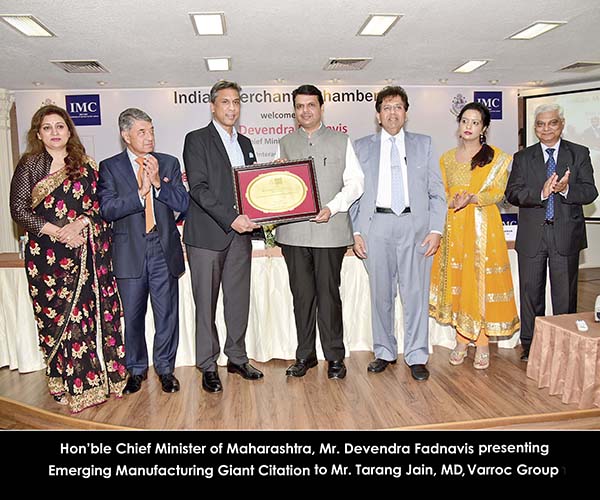

Debi Prasad, meanwhile, had the rare honour of being appointed a member of the Constituent Assembly, the august body tasked with the responsibility of drafting the Constitution of free India. Earlier, in 1925, he had co-founded the Indian Chamber of Commerce together with G D Birla and others, and in 1926, had established the Federation of Indian Chamber of Commerce and Industries, in cooperation with Sir Purushottamdas Thakurdas and G D Birla.

After Kali Prasad, the next to join Khaitan & Co was Durga Prasad. Cast in the same mould as his brothers and a consistent topper as well, he earned a first class first in both his bachelor’s and master’s degrees and then in his Bachelor of Law and attorneyship exams as well. Thus initiated, he joined his brothers at Khaitan & Co, as an attorney in 1917. After heading the firm for a few years—this was when Debi Prasad had to dedicate his services exclusively to G D Birla after Birla Brothers was formed in 1919—he served as the councillor of Calcutta Corporation and then went on to head several commercial bodies as president, including the Indian Sugar Mill Association and the Tanners’ Federation of India. He also served as the vice-president of the Indian Chamber of Commerce, before joining Birla Brothers, where he rose to be the vice-chairman of Bharat Insurance Company. Later, he dedicated his time and efforts towards building his manufacturing business. He passed away in 1943.

Naurangrai’s fifth son, Gauri Prasad’s descendants were to own Calcutta-based tea major, Williamson & Magor. Gauri Prasad was followed by Chandi Prasad who again was extremely sharp academically. Unfortunately, his untimely death left the Khaitans bereft of yet another brilliant mind, who might have possibly taken the family name to still loftier heights.

Bhagwati Prasad, the youngest of the Khaitan brothers, whose illustrious career and association with the firm stretched several decades, made his acquaintance with the city of Calcutta as a primary school student of the historic Vishuddhanand Saraswati Vidyalaya. His special aptitude for learning took him through a bachelor’s degree from Presidency College to a law degree from the University of Calcutta, before he joined Khaitan & Co in 1928. In 1930, he was inducted as attorney-at-law at the Calcutta High Court, after which, in 1934, he was appointed a notary by the Archbishop of Canterbury. A well-rounded man given as much to academics and philanthropy, he was an epitome of fair practice in a field generally thought of as being otherwise. His relationship with his clients was more like that of a friend and confidant, rather than paid counsel. This, among other reasons, was to draw clients to Khaitan & Co in their hordes—especially fellow Marwari businessmen and industrialists—ushering the firm into the glory days it has enjoyed since.

In the meanwhile, in 1928, the firm’s offices shifted to the landmark Emerald House (which also was in Old Post Office Street). Owned by the Bangurs of Calcutta, in 1979, both the lessors and the lesees decided that Khaitan & Co would remain the tenants of the premises for its entirety. Almost a century later, Emerald House continues to be Khaitan & Co’s head office, now housing plush meeting rooms where the lawyers of the firm meet their clients, in addition to regular offices of the firm that have witnessed so much of its history.

Spearheading growth

Bhagwati Prasad’s grooming, both professional and personal, had taken place under the guidance and tutelage of some of the best legal minds of the time, including Ishwar Das Jalan, who was a part of the firm, and, of course, his own brothers, who were icons of the legal fraternity. Bhagwati Prasad was not exactly money-minded. On the contrary, he was often thought of as being generous to a fault. An excellent strategist, he could argue, persuade and get the better of his opposition with his consummate skills as an attorney. As the head of Khaitan & Co, he commanded both awe and respect, but at the same time he was compassionate and an excellent tutor, whose proclivity for hard work, fair play and respect for the legal profession was worthy of emulation. Clients trusted him to the hilt, and both they and fellow colleagues took his advice without demur. One could see top industrialists breeze in and out of his Ballygunge Circular Road residence every morning in the heyday of his career.

New inductees looked to honing their skills under him, and working for him was thought of as the best possible on-the-job training for aspiring attorneys. Many of those who worked under him achieved unusual competence in the field, including names like Ram Kishore Choudhury and more famously Sitaram Jhunjhunwala, whose sons and grandsons still work for the firm. Bhagwati Prasad, in fact, had built such a formidable team that the annals of Khaitan & Co are replete with landmark cases fought and won by the firm, including Sahu Shanti Prasad Jain’s alleged FERA violation case in the ‘50s; the trial of former prime minister, Indira Gandhi, for alleged offences and excesses committed during the Emergency; the case of Sonia Gandhi’s Indian citizenship being challenged; among scores of others.

Bhagwati Prasad’s contribution in the area of philanthropy was remarkable too. Apart from being the founder president of Ballygunge Shiksha Sadan, a well-known girls’ school in Calcutta, he was also the president emeritus of S V S Shikshayatan College and the trustee of a number of public charitable trusts. He was also the founder president of the Law Research Institute, a body associated with assisting those aspiring to pursue the legal profession and also with supporting and developing legal education. The credit of inspiring the first Marwari women to study attorneyship also goes to him.

The long arm of the firm

Like most other firms, Khaitan & Co too was a partnership firm, where work was shared between partners, articled clerks and lawyers. It had dedicated teams to handle various classes of litigations, but all cases, large or small, received the same dedication and importance which stood the firm in good stead in the long run. Sincere and trustworthy, Khaitan & Co also took on and handled all kinds of legal issues, no matter how complex. The firm’s fortunes especially began to rise after Independence, when the Indian Income Tax Act evolved, the Companies Act came into being, new industries were set up, both the public and private sectors burgeoned, collaborations were forged (with both national and international companies) and the Indian industry grew exponentially.

These brought more work for Khaitan & Co, a fair share of it coming from Marwari business houses. Many of them reposed blind trust in the firm and many still do, thanks to Khaitan & Co’s unrivalled reputation and intimate understanding of the Marwari mindset, Marwari family structures, the Marwari ethos, Marwari family values and intent.

In the ’70s, Calcutta went through a sea change with the communists taking over and an anti-capitalist sentiment pervading the state which had most corporations pack their bags and relocate to other cities. Khaitan & Co did likewise, but did not leave bag and baggage. Instead, offices were opened in major metropolises, starting with New Delhi in the seventies (where Om Prakash Khaitan, another grandson of Lakshmi Narayan was in charge), Bangalore (now Bengaluru) in 1993 (where Rajiv Khaitan was in charge) and Mumbai in 2001 (where Bhagwati Prasad’s grandson, Haigreve Khaitan was in charge).

As of today, Khaitan & Co is a full-service law firm and the senior most partner is Bhagwati Prasad’s son Pradip Kumar Khaitan (Pinto to his friends), who over the last four-and-a-half decades has acquired a formidable reputation like his father. The firm boasts 115 partners and directors and over 500 fee earners (including partners and directors) across its four offices. It exercises a global influence, thanks to its good working relationships with international firms, and is capable of advising any client in India or elsewhere in the world, in any matter. Among its areas of practice include mergers, joint ventures, acquisitions and sales of controlling interest, minority sales, investment, pre-IPO placements, public takeover offers, hostile takeovers, management buy-outs, business transfers and asset sales in both domestic and cross-border transactions. And with that, the century-old legend called Khaitan & Co not just lives on but continues to conquer new grounds as it marches towards a double century.